I am the black sheep in my family. I have pushed back against the dysfunction in our family since childhood. I asked for my needs to be met. I was ignored or ridiculed. I asked for safety. I was thrust repeatedly into harm’s way by my parents’ ignorance and obliviousness. I sought relief from my pain. I was labeled histrionic and, most frequently, “dramatic.”

To protect my mother, the near and extended family clustered around her belief system as if it was gospel, and she the patron saint of non-conformity. “We weren’t dysfunctional,” the chorus would crow in unison. “We are special.”

Our academic and business achievements and worldwide travel thinly covered the truth of a family awash in pain and self-loathing and mutual disrespect. Our family was the living epitome of cognitive dissonance. We acted one way – successful and self-confident, especially in the public arena – and felt completely other in the tight-knit family system. Scared and broken little girls each and every one of us.

Tight-knit we were. To reinforce the themes of superiority and hide the abject vulnerability of each member of the system, no one outside our circle was permitted to get very close. Unless, like us, they were broken and needy and in awe of my mother. then they were granted full admittance to the so-called inner circle and gratefully did my mother’s bidding.

Sinead O’Connor died this week. I had mixed feelings. The musicianship of this Irish wildcat was unmatchable. But her very public pain and defiance against her own dysfunctional and abusive childhood alienated her from a large part of society.

The very public act of tearing in half a picture of the Pope that had hung in her wretched mother’s bedroom was widely misinterpreted. Many of us seeking answers to our upbringings know the misunderstanding that can come when sharing our private pain publicly. It is frequently misunderstood and rejected.

Especially when it treads on other people’s sacred cows and belief systems. Note how long it took the world to take sexual abuse in the Catholic church seriously. I know for a fact many Catholics do not believe beloved priests are capable of such heinous acts.

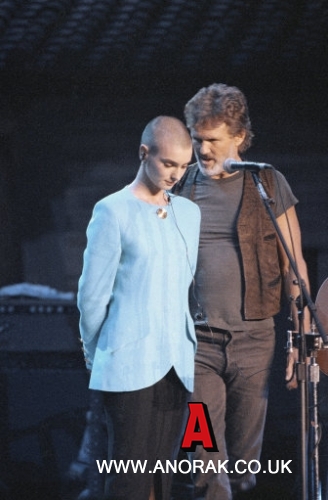

These song lyrics were recently shared in the wake of Sinead’s death. A tribute song Kris Kristofferson write for her when she was booed off the stage at a Bob Dylan concert in 1992.

Abused adult children desperate for answers and relief from their pain may see themselves in these lyrics. God bless Sinead O’Connor. She sure wasn’t wrong in her belief that child abuse is the fount and mother of immeasurable untold evils in this world. Would that she had an easier ride on this planet. She certainly will now. RIP.

Sister Sinead, Kris Kristofferson (2009)

“I’m singing this song for my sister Sinead

Concerning the god-awful mess that she made

When she told them her truth just as hard as she could

Her message profoundly was misunderstood

There’s humans entrusted with guarding our gold

And humans in charge of the saving of souls

And humans responded all over the world

Condemning that bald-headed brave little girl

And maybe she’s crazy and maybe she ain’t

But so was Picasso and so were the saints

And she’s never been partial to shackles or chains

She’s too old for breaking and too young to tame

It’s askin’ for trouble to stick out your neck

In terms of a target a big silhouette

But some candles flicker and some candles fade

And some burn as true as my sister Sinead

And maybe she’s crazy and maybe she ain’t

But so was Picasso and so were the saints

And she’s never been partial to shackles or chains

She’s too old for breaking and too young to tame.”